|

| Harry and Caresse Crosby at desk in library, 19 Rue de Lille, Paris |

Harry Crosby – hey now heads up people today marks the 127th anniversary of his birth, on June 4, 1898 – Harry Crosby fascinates with his:

* poetry (at first traditional and not particularly original, then ultra-modern, revealing, in the riveting words of Philip Lamantia, “a true dandy of explosively Promethean desire”),

* marvelous diary (Shadows of the Sun, originally published in the late 1920s and 1930, and in a definitive version in 1977),

* exceptional publishing work (the legendary Black Sun Press, done with his wife Caresse),

* all-encompassing Sun-worship,

* life as a World War I ambulance-driver then an expatriate in wild 1920s Paris, with travel, alcohol, opium and an open marriage, and

* disturbing embrace-of-death (even if psychologically explainable), culminating in the tragic 1929 double-suicide (or possibly murder-suicide) of him and his mistress.

That’s a lot. But yes, please wait, there’s more. In addition to all the above, there was Crosby’s resolute self-education through reading, including particularly poetry. It may not sound like much, but may be the most impressive and inspiring of all.

Crosby read a lot (he ultimately amassed a library of thousands of books) and, more than that, from age nine (!) to his death (at age 31) cataloged by hand each book he read, in order, year-by-year. That handwritten notebook with its list of books read is still extant in his widow Caresse’s library-ed papers. It shows approximately 1,050 books read (including repeats) between 1907 and 1929. That’s a healthy average of about 45 per year, though the actual annual count ranged from about 30 to more than 100 (the latter in both 1926 and 1927). Crosby’s books-read list offers unique insight into his wide-ranging and evolving mind and passions. It’s a kind of detailed map of his interests and noetic spirit.

It’s particularly apt to celebrate Crosby’s reading today because, as it happens, among the books he read exactly 100 years ago – during the first few months of 1925 – were a novel, a poetry collection, and a poet’s collected works that turbo-charged major changes in his literary imagination, views, and poetry. In other words, it’s the centenary of the reading that to a great degree made Crosby the poet he became.

+++

+++++

+++

Crosby’s Foundational Poetry Reading

Crosby’s remarkable early 1925 run of reading – discussed in detail below – was built on a strong foundation of previous years’ reading, including poetry in particular. In 1917 and 1918, for example, Crosby, while an ambulance driver in World War I France, read (and thought highly of) The Rubáiyát and Robert Service’s Rhymes of a Red Cross Man.

|

| Edward Fitzgerald and Edmund J. Sullivan, The Rubáiyát (1913) |

Crosby also during the war – including after November 22, 1917, when a shell burst vaporized his ambulance (miraculously, he was not physically hurt though shrapnel tore open his good friend’s chest) – read in the Oxford Book of English Verse 1250 - 1900.

According to his biographer, this was Crosby’s “first systematic self-education in good poetry.” Geoffrey Wolff, Black Sun: The Brief Transit and Violent Eclipse of Harry Crosby, 1976, at 68.

Further, in 1922, after having earned a solider’s degree from Harvard and moved to Paris, Crosby declared “poetry is religion (for me)” (Shadows of the Sun, July 28, 1922). That same year, and continuing through early 1923, he systemically read (or re-read) all of Shakespeare, cataloging each play and work in his books read list.

Perhaps most tellingly, Crosby in 1923 assembled his favorite poems, titling the collection Anthology; in 1924, he privately published a small edition of the book, using his full true given name:

Anthology next has sections on, respectively, war (all written during or about World War I, including a dozen by Siegfried Sassoon), and love (all essentially contemporary except for several poems by the late 19th Century’s Laurence Hope), poetic prose (starting with selections from the Bible and ending with six extracts from Franz Toussaint’s Le Jardin des caresses – a combination that neatly points to the reverent erotic tone in some of Crosby’s later poems), French poetry (en français, but including only one poem by Charles Baudelaire and none by Arthur Rimbaud or any 20th century poet), Shakespeare (extracts from the plays, plus six sonnets), English poetry (starting with Chaucer and Milton, then jumping to the romantics and those that followed, ending with Oscar Wilde), and concluded with a section that excerpts from three “lyrical poems”: Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard,” John Keats’ “The Eve of Saint Agnes,” and Edward Fitzgerald’s “The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám” (Crosby at the time considered the latter “the summum bonum of all masterpieces,” as he wrote in Anthology’s introduction).

All the above – and it’s just the highlights of his reading – demonstrates a remarkable dedication to, and diligence in, the study of poetry. This all resulted in a solid – though not particularly adventurous – foundation for what came next, including his (1) declaration, in August 1924 that he was a poet, and (2) reading, in the first months of 1925, of three particular books or authors that revolutionized Crosby’s imagination and literary approach.

+++

+++++

+++

Early 1925 reading: James Joyce’s Ulysses

Preliminarily, and to better set the stage, Crosby began 1925 year by re-reading Gustave Flaubert’s historical novel Salammbô. Then, over the next few weeks he read Theordore’s Gautier’s still compelling 1830s Mademoiselle de Maupin, four books related to World War I – The Love of An Unknown Solider, Sassoon’s War Poems (for the second time), Henri Barbuse’s Le Feu (Under Fire), and Roland Dorgelès’ Les Croix de bois (Wooden Crosses; this latter book caused him to observe (see Shadows of the Sun, February 1, 1925), “above all else we who have known war must never forget war”), and – and this the first of 1925’s revolutionizing reads – James Joyce’s Ulysses.

Per Crosby’s library inventory (also library-ed in a special collection) and his diary, he read a later, 1924 Shakespeare and Company edition of the book, issued with a white cover:

Crosby’s reading of Ulysses came several years after the novel was serialized in The Little Review and three years after it was first published as a book.

While Crosby was a few years late to the Bloomsday appreciation party, he was obviously deeply impressed. After his early 1925 reading of Ulysses Crosby began using Joycean neologisms, portmanteaus, or unusual words in his poems. His first collection,

Sonnets for Caresse, published in October 1925 (then reprinted with some variations in 1926 and 1927), is largely conventional but includes plenty of lexical play a la

Ulysses. In the first few poems, for example, are “sunnygolden,” “rustcorroded.” “luisant,” and “slowpulsing,” and, similarly, in the last several poems, “fairfragrant,” “awayaway” and “neverwavering.” Other poems include other examples, such as “phantomfevered” and “monstrousmarching.”

While Crosby’s soon enough moved away from such emulation, Joyce’s wordplay plainly liberated his imagination and stuck with him. For example, well over a year after he’d first read the book, he diary-ed (see

Shadows of the Sun, June 9, 1926), that “before going to bed” he “studied Joyce words in Ulysses,” listing “ungirdled, smoke-plume, upwardcuruving, sandflats, chalkscrawled, harping, crunching, trekking, winedark, redbaked, miscreant, firedrake, orifice, lesbic, cartload, [and] turfbarge.” Ten days later, he called Joyce “the greatest of them all” (see

Shadows of the Sun, June 19, 1926). This opinion never changed.

In 1928 – on Bloomsday itself yes indeed, my friends – Crosby went “to the Rue Richelieu to buy for a hundred dollars a magnificent copy of the first edition of Ulysses signed by Joyce and bound in a magnificent blue binding . . .” (

Shadows of the Sun, June 16, 1926):

In 1929, in an essay titled “Observation Post”, Crosby again declared his allegiance to the genius of Joyce, calling him “the Great Alchemist of the Word, the Paracelsus of Prose, the Transmuter of metal words into words of gold” (and that same year, he and Caresse, via their Black Sun Press, published Tales Told of Shem and Shaun, three fragments from Joyce’s Work in Progress, which eventually became Finnegans Wake).

+++

+++++

+++

Early 1925 reading: Charles Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal

After reading his wife Caresse’s verse collection, Crosses of Gold, Crosby in early 1925 read Charles Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil). He’d read at least some of the poems therein previously, having quoted one in a 1922 and another in a 1924 diary entries, and included a third poem from the book in his 1924 Anthology. But, per his library inventory, Crosby in early 1925 appears to have acquired then read a new edition of the book that had just been released by a Paris publisher:

.jpg) |

| Les Fleurs du Mal (Libraire Alphonse Lemerre, Paris, 1925) |

Crosby clearly was deeply impressed with this poetry. On April 9, 1925, Crosby wrote in his diary, “Baudelaire’s birthday and wrote in his honor a Sonnet . . . .” The poem, included in Crosby’s first book of poetry, Sonnets for Caresse (first published in October 1925), is not only named for the French poet but name-checks Les Fleurs in its final line:

.jpg)

Crosby’s biographer Geoffrey Wolff (see Black Sun at 139-140) suggests this poem follows from Les Fleurs du Mal’s “Spleen” and that definitely seems right for many reasons, including Crosby’s reference to “your blackest flag” in the first line of the second stanza, a clear echo of the phrase “son drapeau noir” that ends Baudelaire’s poem.

Per his diary, in late April 1925 Crosby honored Baudelaire by visiting his grave in Paris. More than that, later that same year (see Shadows of the Sun, November 19, 1925), he “[b]ought a first edition of Les Fleurs du Mal for twelve hundred francs . . . .” His library inventory does indeed include a copy of that 1857 edition.

.jpg) |

| Les Fleurs du Mal, Poulet-Malassis et de Broise, Paris, 1857 |

Crosby’s purchase of first edition, I submit, is a no-doubt sign of his love for the poetry (and his bibliomania as well!). (FYI,

the least-expensive copy of this book today is priced at approximately US $28,000.)

Crosby continued to re-read

Les Fleurs du Mal, quoting it twice in February and twice again in July 1926 diary entries. Even more tellingly, he wrote a series of poems that in early 1927 he published in his second collection,

Red Skeletons, which Wolff (see

Black Sun at 187) calls “a decadent imitation of Baudelaire.”

Imitation or not, the Baudelarean influence in Red Skeletons is clear, starting with one of the book’s epigraphs, taken from Les Fleurs’ “Causerie” [“Conversation”]:

Ne cherchez plus mon coeur; les bêtes l'ont mangé.

(Do not search for my heart anymore; the wild beasts have eaten it.)

More generally, the book’s poems are full of Baudelarean decadence, introspection, and morbidness. True, Crosby’s language and the sonnet form used are sometimes forced or clunky. Still, there’s an appealing sincerity and earnestness to the poems, including I submit, in “Noir,” reproduced below. The image that ends the poem’s first stanza – the pink (presumably blossoming) almond trees against the silver of a far-off sea – is both memorable and outré enough to effectively set up the pivot to the death and dark of the concluding lines:

The plot twist here is that Crosby almost immediately after Red Skeletons was published disavowed its literary approach (see Black Sun at 193), and never embraced it again. In the last year of his life, he burned eighty copies of the book in a bonfire, and shot bullet holes through four other copies (see Shadows of the Sun, March 9, 1929).

+++

+++++

+++

Early 1925 reading: the poetry of Arthur Rimbaud

Per a Crosby diary entry, on April 19, 1925, his cousin Walter Van Rensselaer Berry – an international lawyer, man of letters, friend of Proust and Henry James, and fellow Paris resident – suggested he read Rimbaud.

Voila! Crosby got right on it. On April 23, just a few days after his cousin’s suggestion, he quoted Rimbaud’s schoolboy essay valorizing the strange life of poets (“let them live . . . Let the world bless the poets”) in his diary.

Crosby’s Books Read list shows he consecutively read three Rimbaud volumes: Premier Vers, Les Illuminations, and Une Saison En Enfer which had been published as a set in Paris in 1922:

|

| Premier Vers, Les Illuminations, Une Saison En Enfer : Éditions de La banderole, Paris, 1922. |

Those three books look sweet, yes? His copies of these books, are at the Ransom Center in Texas; he signed and dated the first volume April 1925.

Per his diary, Crosby finished the three books by May 1, 1925, when he reported he had begun Jane Austen, quoting the man-saves-the-injured-woman scene from early in Sense and Sensibility and remarking, “how quaint after Rimbaud.” Indeed! To emphasize the contrast, Crosby quotes (in French, natch) the visionary declaration found in the “Adieu” section of A Season in Hell:

Un grand vaisseau d’or, au-dessus de moi, agite ses pavillons multicolores sous les brises du matin. J’ai créé toutes les fêtes, tous les triomphes, tous les drames. J’ai essayé d’inventer de nouvelles fleurs, de nouveaux astres, de nouvelles chairs, de nouvelles langues.

[A great golden vessel, above me, waves its multi-coloured flags in the morning breeze. I’ve created all the feasts, all the triumphs, all the dramas. I’ve tried to invent new flowers; new stars, new flesh, new languages.]

Rimbaud’s influence on Crosby work was profound but did not result in the immediate emulations and imitations as did the reading of Joyce and Baudelaire. That said, Crosby later in the year – see Shadows of the Sun, November 15, 1925 – acted on his love of Rimbaud in a most astonishing way: “Went out to buy silk pyjamas but came back with a first edition of Les Illuminations very rare as there were only two hundred copies edited by Verlaine and the price was five hundred francs.”

|

| Les Illuminations. Notice Par Paul Verlaine. La Vogue, Paris,1886 |

Incroyable! Today, that book would cost between approximately $29,000 and $44,000.

Rimbaud stayed with Crosby, even as he read hundreds of other books in the years that followed. In July 1927, for example, he packed Edgell Rickword’s pioneering 1924 study Rimbaud – Boy and Poet when he traveled to Spain. On July 10, 1927, Crosby wrote, “I believe with Rickword that all the great visionary poets have been more than human in their moral strength and their demoniac fury of self-belief.” In August 1927, he (in his diary) singled out “Le Bateau ivre” as the best poem written before the mid-1920s.

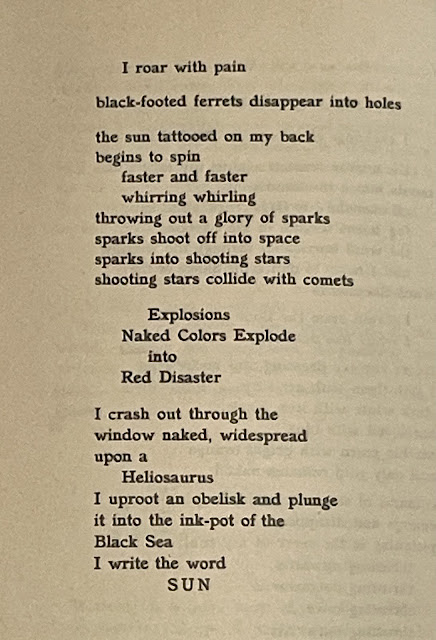

In September 1928, Crosby, in a diary entry, said he’d written a poem – “Assassin” – influenced in part Rimbaud’s “voici le temps des assassins” [“now is the time of the Assassins”], from the very end of “Matinée d'ivresse” [“Morning of Drunkeness”] in Les Illuminations. In fact, Rimbaud’s line serves as the epigraph to “Assassin,” which was first collected in Crosby’s Mad Queen (1929). The poem’s an eight page, ten-part combo of prose and free verse. Importantly, it’s not an imitation of Rimbaud but rather arises from the same kind of riotous almost superhuman and fevered fervency. Tighten your seat belt and consider, for example, this four-page excerpt from the poem (note: “the Mad Queen” is Crosby’s self-invented Sun-Goddess):

Rimbaud and his poetry are repeatedly invoked in

Mad Queen, including in

the dardanic poems “Stud Book” and “Sun-Testament.” The latter takes the form of a will; Crosby has the Sun bequeath its “firecrackers and cannoncrackers” to Rimbaud.

Most definitively, Crosby in an April 1, 1929 diary entry flat-out declared:

I [re]read Une Saison En Enfer and I believe that Rimbaud is the greatest poet of them all—bow down ye Shelleys ye Keates ye Byrons ye Baudelaires ye Whitmans for you have met your Master . . . .

A few days later, on April 4, 1929, he diary-ed that he’d agreed to help fund and edit

transition, having told founder Eugene Jolas the magazine should be based on the Rimbaudian “policy of revolution of attack, of the beauty of the word for itself . . . .” Consistent with that, when the “Proclamation” supporting the magazine’s “Revolution of the Word” campaign was published in June 1929,“the hallucination of the word” was a central tenet and Rimbaud was named as the exemplar:

Crosby in June 1929 celebrated his 31st birthday, which was to be his last. As he reported in a diary entry the month before – see Shadows of the Sun, May 6, 1929 – he’d bought himself an early birthday present: “the first edition of Rimbaud’s [Une] Saison En Enfer”:

Once again, incroyable !

Incroyable !

+++

+++++

+++

Are you inspired? I am. Here’s a life, a creative journey, revolutionized by words written by others, by poets, bound in printed books. Books! The example of Crosby as a reader (and book-buyer) – almost exactly a century after it happened – should impress and inspire. Especially today, I suggest, amidst all the texts, emojis, Instas, and Tik-Toks. As Crosby wrote more than once in his diary, “Books Books Books Books . . . [!]”

|

| Bust of Harry Crosby, sculpted by his wife Caresse |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)