Love’s the thing in “The Talisman,” a four-stanza, nineteen line poem by Philip Lamantia. The poem was first published in 1969 and is of course included in The Collected Poems of Philip Lamantia (University of California Press, 2013). And this poem, with love at its center, is most certainly right for today, the 91st anniversary of the birth of the poet whose work I adore. Let’s celebrate by reading – then taking a quick, closer look at – this most marvelous poem:

The Talisman

Only for those who love is dawn visible throughout the day

and kicks over the halo at the pit of ocean

the diamond whirls

all that’s fixed is volatile

and the crushed remnants of sparrows travel without moving

I find myself smoking the dust of myself

hurled to the twilight

where we were born from the womb of invisible children

so that even the liver of cities

can be turned into my amulet of laughing bile

Melted by shadows of love

I constellate love with teeth of fire

until any arrangement the world presents

to the eyes at the tip of my tongue

becomes the perfect food of constant hunger

Today the moon was visible at dawn

to reflect o woman the other half of me you are

conic your breasts gems of the air

triangle your thighs delicate leopards in the wood where you wait

+++(+)+++

“The Talisman” opens strong with a bold luminous assertion:

Only for those who love is dawn visible throughout the day

That’s a declaration that’s stuck with me for years now, and how could it not? It powerfully conveys that love brings fresh, sustained visions, and the certainty with which it’s asserted persuasively sweeps you into the poem, which with quick rhythmic lines then showcases a series of surrealist images and actions, some drawn from classic surrealist ideas, including the first stanza’s

All that’s fixed is volatilewhich echoes a fundamental precept explicated by Andre Breton in the first chapter of L’Amour fou (Editions Gallimard, 1937), translated as Mad Love (University of Nebraska Press, 1987):

The word ‘convulsive,’ which I use to describe the only beauty that should concern us . . . .” [ . . . ] Convulsive beauty will be veiled-erotic, fixed explosive, magic-circumstantial, or it will not be.Much else in the poem, such as the mix of interior awareness, vibrant action, and what I’ll call “elsewhere” in the last three lines of the second stanza–

I find myself smoking the dust of myself–strikes me as quintessential Lamantia: the words dust, womb, invisible, and children are among those that recur in his poetry (by the way, I continue to hope for a concordance to his works). Other they-can-only-be-Lamantia images, it seems to me, are “my amulet of laughing bile” (in the second stanza, and presumably the titular talisman), then “teeth of fire” and “the eyes at the tip of my tongue” in the third stanza.

hurled to the twilight

where we were born from the womb of invisible children

In the final stanza, Lamantia brings back the dawn of the poem’s first line:

Today the moon was visible at dawnand by reporting on what he presumably saw just a few hours earlier Lamantia also neatly returns us to the right here, right now. It’s a lovely reverie-bloom of an image, bringing together, as surrealists sometimes do, the opposites of night and day. “[T]he moon . . . at dawn” might also to be verisimilitudinous detail of what was seen after spending a night at play and in conversation, a possibility heightened by the concluding lines identification of a particular woman as the animating source of the love-energy that has fueled the poem.

The beloved’s importance and delights are marvelously celebrated in the poem’s last three lines. Lamantia first directly declares her spiritual and psychological value (“the other half of me you are”) then uses cadenced references to her breasts and thighs (“conic your breasts” / “triangle your thighs”) as a poetic springboard for vivid praise. The geometry trope reminds that Lamantia had an avid interest in that field, including its philosophical elements.

The rousing images that conclude the poem suggest and celebrate his beloved’s rare and exalted beauty (“gems of the air”), and, via a metaphor from the animal world (“delicate leopards in the wood”), certain of her pardine qualities, including, if I may I run reverie-wild with the image, a fine, fierce intelligence, lithe agility, nocturnal energy, and patient self-assurance:

Today the moon was visible at dawnWhat a lovely, loving poem! Yes I said yes I will yes!

to reflect o woman the other half of me you are

conic your breasts gems of the air

triangle your thighs delicate leopards in the wood where you wait

Happy Philip Lamantia Day, and

¡Viva Lamantia!

+++(+)+++

“Today the moon was visible at dawn . . .”

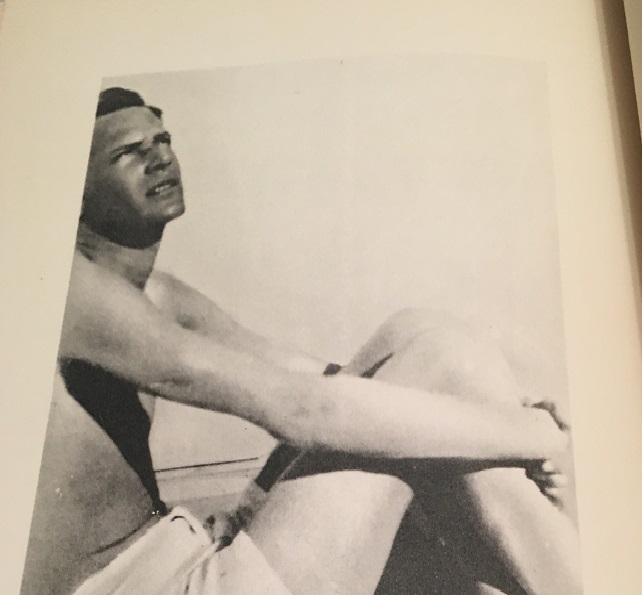

Philip Lamantia

February, 1999

Beyond Baroque / Venice, California

Photograph by Michael Hacker

+++(+)+++

+++++(+)(+)(+)+++++

+++(+)+++